From the founders

Look at this image.

Somewhere in the foothills of eastern Spain, a prehistoric artist climbed into a cave and painted what you see here: a human figure scaling ropes toward a wild bee nest, basket in hand, surrounded by angry dots representing bees. That was 8,000 years ago. The figure isn't a beekeeper (“beekeeping” didn't exist yet.) This is a honey hunter. Taking what they could and moving on.

We've been thinking about the full arc of beekeeping history lately.

Actual beekeeping—maintaining colonies rather than raiding them—started in Egypt around 2450 BCE. Beekeepers moving hives up and down the Nile to follow blooms. Managing hundreds of colonies. Systematic extraction methods.

Medieval monasteries kept bees for wax (required for church candles) as much as honey. Beekeepers often killed colonies at harvest because they couldn't access comb any other way.

Modern beekeeping emerged in the mid-1800s when movable frames made routine inspection possible. The 20th century brought commercial scale and migratory pollination. Varroa arrived in the 1980s and changed everything again.

Each era adapted the practice to its circumstances and priorities. Ours will too.

— The Primal Bee Team

10,000 years of keeping bees

Honey hunting persists today among the Gurung people of Nepal, who climb cliff faces on rope ladders to harvest from giant Himalayan honeybees. The techniques would be recognizable to whoever painted those Spanish caves.

But let’s take it way back to the beginning…

Egypt: where beekeeping began. The earliest evidence of organized beekeeping comes from Egypt around 2450 BCE. Relief carvings show beekeepers working with cylindrical hives, using smoke, extracting comb, pressing honey. They transported colonies up and down the Nile to follow seasonal blooms, sometimes managing hundreds of colonies. Honey served as sweetener, medicine, preservative, religious offering, and tax payment.

Medieval Europe: honey and wax. Beekeeping centered on two products. Honey was the primary sweetener available to most people. Beeswax was required for church candles—monasteries became centers of beekeeping expertise. Most beekeepers used skeps—coiled straw baskets placed open-end-down—which had been in use for nearly 2,000 years. Management was hands-off by modern standards, and the harvest typically killed the colony. Without access to individual combs, beekeepers extracted honey by destroying the hive structure after suffocating the bees with sulfur smoke.

The movable frame. Throughout the 1700s, beekeepers experimented with designs that allowed access to individual combs. François Huber's "leaf hive" (1789) was an early breakthrough—combs could be examined like pages in a book. Lorenzo Langstroth's 1852 patent unified these efforts by systematically applying "bee space"—the specific gap that bees leave open as passageways. His hive design made routine colony inspection practical for the first time. Beekeepers could examine brood patterns, assess queen health, check for disease, and harvest honey without killing bees.

Commercial scale. The movable-frame hive made it possible to maintain colonies year after year. Operations grew from dozens to hundreds to thousands of colonies. Migratory beekeeping developed as beekeepers learned to move colonies for pollination services. The California almond industry now requires roughly two-thirds of all managed honeybee colonies in the United States each February.

Varroa. The mites spread globally during the 1970s and 1980s, reaching the United States in 1987. Untreated colonies typically die within one to three years. Managing Varroa became a central concern of modern beekeeping. Annual colony losses have averaged 30-40% in recent years.

What's next: thermodynamics. Recent research is focused on how bees regulate temperature within the colony—and how hive design can support or hinder that process. Bees in poorly insulated hives expend more energy maintaining optimal temperatures, leaving fewer resources for foraging and honey production. A new generation of hive designs (wink wink) is prioritizing thermal efficiency. It may be the next major step in the evolution of beekeeping.

🐝 Two hives, one city, a whole lot of buzz.

🎙️ Our very own Dr. Jason Graham talks swarms, queens on a diet, and why bees are smarter than we think.

🔥 The hive can hold 95°F—until the planet won’t.

👑 Turns out queen bees are just playing to their strengths (or tongues).

🐝 That’s a wrap!

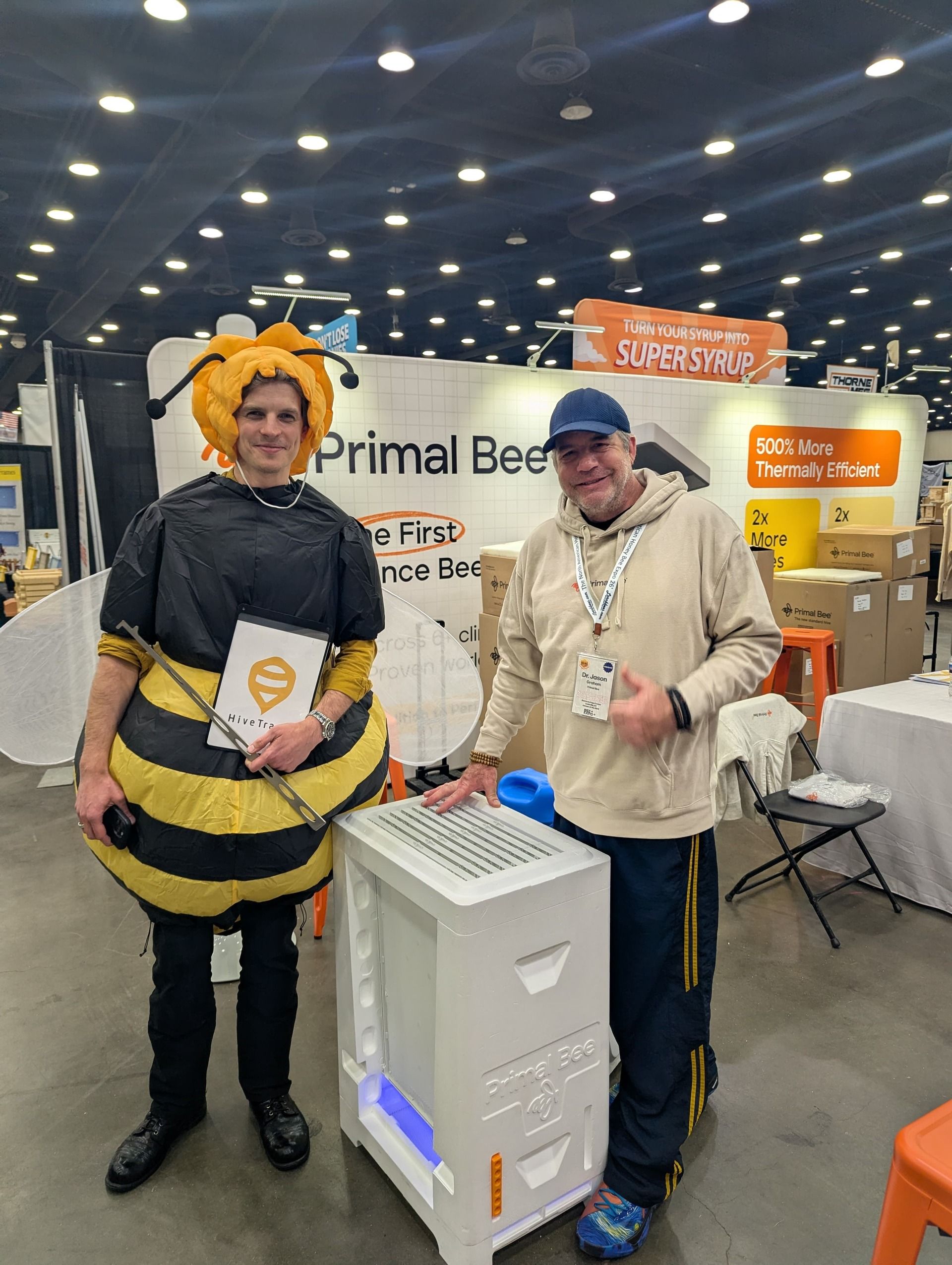

We just got back from NAHBE and ABF and had an incredible time seeing old friends and meeting new ones - many of whom joined the Primal Bee family while we were there.

To everyone who stopped by our booth, asked questions, shared stories, and took a chance on a new kind of hive: thank you. We're excited to watch and support your progress with your Primal Bee hives.

A quick ask: please keep us posted!

Share your pics and videos beekeeping in your Primal Bee hives so we can compare notes, continue to improve, and learn from each other.

Until next time

History is useful because it shows what changed and what didn't.

Beekeeping adapted when wild colonies became scarce and people started keeping bees closer to home. It adapted when the movable frame made inspection possible. It adapted when commercial pollination created new economic incentives. It adapted when Varroa arrived and forced everyone to rethink management.

Each transition looked different from the one before. The circumstances changed, and the practice changed with them.

We're somewhere in the middle of another adaptation now—one that includes new research into hive thermodynamics and how hive design can support bees' natural temperature regulation.

Until next time,

The Primal Bee Team 🐝